WWC: Wired, Wired Country – by Dhiren

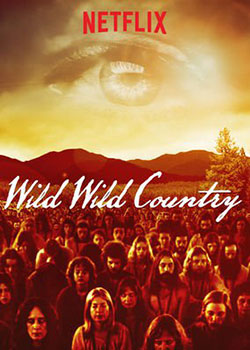

The first thing is, have you binge-watched it yet or not? Just tracking the publicity leading up to Netflix’s launch of the 6-part docuseries, ‘Wild, Wild, Country’, had certainly made me very eager to see it, writes Dhiren.

Apart from the potentially huge international audience, I was sure that there would be thousands of former ranch residents and visitors fascinated to see a documentary of events which they had lived through. I guessed that I was not alone in feeling a certain frisson, much like you might have just before watching a big-budget movie focussed on members of your sometimes wonderful, sometimes horrendous, extended family. Apart from anything else, many sannyasins would be surely looking forward to a quirky visual (and emotional) time-trip back to the place that was home for more than four years.

The Hollywood Reporter, in an astonishingly balanced review, had promised that we would want to binge-watch it, so well-made it was.

The directors, in the three interviews I saw, came over as smart young guys, genuinely interested in presenting what they call an ‘almost forgotten American saga’. They spoke of sannyasins as ‘disciples’, members of a ‘spiritual/religious movement’, of the ranch as an extraordinary experimental ‘utopia’ which had nevertheless been doomed from day one. They acknowledged that the prevailing American conservatism had early on ‘branded’ an entire community as a dangerous cult. They talked of the ‘crazy’ events which led up to criminal acts and of the ‘war’ that ensued in terms of a culture clash – for once, not in terms of a bunch of sex-crazed cultists getting their just deserts.

They had been given 300 hours of unseen archive footage from the time, the visual richness of which convinced them that they were on to a winner. They seemed almost touchingly open-minded about how they had wanted to present deeper aspects of the story in documentary form.

For many sannyasins, all this will be vastly refreshing after years of mainstream media treatment about the Ranch – and Osho in general – which has been drenched in cliché and flooded with what would now be called ‘fake news’. Chapman and Maclain Way, the directors, promised to lay out the story in such a way that viewers will have to reflect and not rely on facile interpretations of the Rajneeshpuram story. Intriguingly, they even said that they wished it could have been a 20-part series, since they had so much more fascinating footage and interviews which all had to be whittled down to a mere 400 minutes.

That was all pre-binge of course. Post-binge, I would say that they have largely succeeded in their goals, and should be thanked for the new clarity they bring to what is still a hugely controversial story. But it’s a stirring, intense 6 hours which reveals little of the inside story and in, my view, also misses some key elements.

Why was there no real discussion of the accusations levelled against Sheela? What about the well-reported admission by US Attorney Charles Turner that there was no evidence to link Osho with any of the crimes that were committed by Sheela and her gang, and that the whole goal, from the Government’s point of view, was to get rid of Osho so as to destroy the commune? The filmmakers would have had little interest in meditation or the motivations that kept us working at fever-pitch both at the ranch and in communes all over the world; their approach was to expose the dynamics of power and the weird ways in which the protagonists came to resemble each other as they destroyed the commune both from the inside and from the outside. And they draw some subtle comparisons with the hateful polarisation going on in the USA of 2018.

There is an important quote from Sunshine early on: “The way that your enemies fight is what you become, so pick your enemies carefully.” Sheela gets far too much of what she always craved: the spotlight, and her self-serving narrative still gets to dominate the agenda. There is no mention of the allegation that Sheela was often being pumped with drugs by her nurse Puja, to keep her going.

Another key element which has got lost in the telling is how Osho had already started to expose Sheela’s tyranny in 1984 in a discourse shortly after he started giving talks in his house to small groups of people. The video tape of one particular talk in which Osho talked directly about Sheela’s behaviour in a very critical way never came to be shown the next night in the Mandir as those talks given in his house usually were. The official explanation was put about that this was because of ‘technical difficulties’ – a blatant lie. In fact it was a clear indication of Sheela’s direct interference with the masters words, purely out of self-preservation. This is not hearsay – I was one of those present at that particular evening talk. My girlfriend at the time lived in Osho’s house because of her essential job, and we knew that my townhouse (the only place that we could spend any time together) was being bugged and had to act accordingly. To us, it was clear that it was Osho’s initial exposure combined with Sheela’s rabid jealousy of anyone who might have access to Osho which prompted her to leave Rajneeshpuram.

We also fail to see how the persuasive reach of American power continued to target Osho himself as he was harried and arrested again and again on the ‘world tour’ before he arrived back in India for the last time. Between the lines, it’s there of course, in the blatantly hateful glee that Oregonian politicians still take in recounting how Osho was made to be the scapegoat and dragged in chains all over the country before being returned to Portland. The long game was clear: a vindictive attempt to wipe this man off the planet and destroy every last shred of his credibility and rebellious legacy.

The fact that it cost Osho his health and almost certainly his life gets lost in some very selective story-telling. There is no mention of Osho’s suspicions that he had been poisoned at some point on that tortuous tour of American jails: too controversial perhaps? To this day of course, opinion is divided as to how much Osho did or didn’t know about what was going on, and more to the point, why did he allow Sheela to have so much power in the first place. But that’s all it is: opinion, and in my view it’s a red herring.

Having said all this, the Chapman brothers and their whole team deserve praise for the most balanced documentary so far about Rajneeshpuram. They apparently worked for four years on this project and hopefully, based on the mostly positive reviews they are getting for their work, might one day delve a little deeper in another series.

Perhaps in a second series we might get to hear the more personal aspects of the story, from the people who lived and visited there. We might also get to acknowledge how many of us ignored our own doubts about Sheela’s increasingly deranged megalomania. In love with our own versions of a dream-city of enlightened Osho’s people, we were coerced through fear of expulsion, and so we all played our part in the drama that emerged.

We might get to reflect on what could be learned. Krishna Prem (Jack Allanach) puts it brilliantly in his memoir, Osho, India and Me, “We built an amazing city and watched it being destroyed by Sheela and her “coterie of selfish, hard-hearted, power-hungry women enforcing a single rule: submit in silence or leave… she ruled out of a lust for power laced with paranoia and a vision of herself as a modern-day maharani of an empire high in the Oregon desert. It was a stunning lesson in how power corrupts, in the heights of psychosis to which a deluded and deranged ego can arise.”

- Log in to post comments

- 8 views